Falling into the Augmented Wonderland:

The history of Art and Technology, in relation to Augmented Reality as an emerging artistic medium. (2020)

︎︎︎

CONTENTS

1) Introduction

2) Chapter One—A brief history of augmented reality.

3) Chapter Two—History of Art and Technology in exhibition spaces.

4) Chapter Three—The Rise of Augmented Reality as an artistic medium.

5) Conclusion

INTRODUCTION

![]()

Augmented reality (AR); most commonly associated with the release of Nintendo's "Pokemon Go", rose the medium's relevance in the summer of 2016. With over a billion downloads as of February 2019, the game has one of the highest number of AR game users of all time. However, this emerging technology is more than just a gaming gimmick. In my practice of graphic design, I have witnessed increasing levels of this technology being used in company branding, such as the work being created at design studio Widen + Kennedy’s Department of New Realities. This has intrigued me to learn more about the origins of the field. In a world where screens are more abundant than ever before, the thought of digital information merging itself with the quotidian lifestyle does not seem an overly distant improbability. It’s contemporary application in art institutions is also fascinating, and leads me to wonder, as artists have become so familiar with digital technology, how will they use augmented reality as an expressionist tool?

Prior to exploring the implications of AR, it is essential to first outline the parameters of the technology and how it differs from other visual mechanics that we experience. Commonly misunderstood for its cousin, virtual reality (VR), both fall under the bracket of the “mixed reality continuum” (Miligram, Kishino, 1994, p. 83) coined by Milgram and Kishino as the “[…] merging of real and virtual worlds somewhere along the “virtuality continuum” which connects completely real environments to completely virtual ones.” (Miligram and Kishino, 1994, p.83). This idea is illustrated more clearly in Figure 1[Right] that shows how MR captures all possible combinations of real and virtual environments.

![]() The two most familiar methods

of viewing AR are either through a smart phone, after downloading an app, or

tech known as ‘smart glasses’, where the lenses are additionally a screen. An

appropriate example of the latter, would-be Google Glass, released in 2014; one

of the first of its kind that was available to the public. Wearers could

communicate with the internet through natural voice commands, allowing them to

view standard applications like the weather, a social media timelines or

video-record what they were seeing. The software running in the machine often

uses an object in the real world as an anchor, and from there projects a

digital object onto the screen. Through having a transparent background or

using a live camera feed, the projection merges into the environment as if it

was actually there.

The two most familiar methods

of viewing AR are either through a smart phone, after downloading an app, or

tech known as ‘smart glasses’, where the lenses are additionally a screen. An

appropriate example of the latter, would-be Google Glass, released in 2014; one

of the first of its kind that was available to the public. Wearers could

communicate with the internet through natural voice commands, allowing them to

view standard applications like the weather, a social media timelines or

video-record what they were seeing. The software running in the machine often

uses an object in the real world as an anchor, and from there projects a

digital object onto the screen. Through having a transparent background or

using a live camera feed, the projection merges into the environment as if it

was actually there.

This blending of two worlds, the physical and the digital, and our relationship with it is what I find fascinating. By witnessing this composite view, an underlying level of uncertainty is felt trying to observe what is ‘real’ and what is not. The user becomes vulnerable to the boundless potential of the digital world, where depending on the ingenuity of an artist, it possible to observe literally anything.

If it is being used in a practical manner, for instance scrolling through your emails whilst commuting to work, this vulnerability is not so clear. However, through the medium of art, that specifically is created to provoke questions and tap into our emotional state, this vulnerability is a gateway that can lead to profound sensory experiences that we have never seen before.

With this small introduction to AR, the first chapter will investigate a brief overview, focusing on the genesis of the technology; Where did AR come from? What were the intentions of the pioneers? Following this, the second chapter will explore how art was influenced by the involvement of digital technology, in an act to understand if an emerging technology will be accepted by institutions. Finally, the third chapter will conclude with an investigation and analysis into contemporary uses of augmented art as a result of changing technological conditions.

CHAPTER ONE—A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUGMENTED REALITY

To comprehend how a technology will advance, it is crucial to understand where it has come from; the pioneers, first engaging with the concept, the boundaries in which it has overcome as well as the experimentalist ways it has been used. As well as this, it is imperative to examine the existing technologies surrounding the field. Hence, this chapter will be brief guide through the extensive history of Augmented Reality (AR) development, analysing significant seminal examples—focusing in particular on Ivan Sutherland’s work that catapulted the essence of AR into reality.

The concept surrounding AR could arguably surfaced over a century ago in Frank Baum’s 1901 illustrated novel “The Master Key: An Electrical Fairy Tale.” Though intended for children, Baum had foreseen the capabilities of electricity, and within the book had fabricated a number of electric inventions; one being a pair of glasses foreshadowing some characteristics we associate with AR. In the text, a boy named ‘Bob’ whose fascination with electricity summons a Demon that bestows him with nine of these electric creations. For the purpose of this essay “The Character Marker” (Baum, 1901, p. 42) is of most use.

“It consists of this pair of spectacles. While you wear them every one you meet will be marked upon the forehead with a letter indicating his or her character. The good will bear the letter 'G,' the evil the letter 'E.' […] Thus you may determine by a single look the true natures of all those you encounter."” (Baum, 1901, p. 42)

Though the “natural forces” that the spectacles are measuring are very likely not to be proven by science, the importance of this example is the instigation of AR. This is the first time in written literature that the concept of projecting graphic information onto a viewer’s perspective has been seen. An interesting point to study in this case is the protagonist’s use and vigilance of the device. In the chapter following being given the spectacles ‘Bob’ deliberates trialling them on his family. However, “[…] a sudden fear took possession of him that he might regret the act forever afterward.” (Baum, 1901, p. 42). In this example, Bob’s “fear” (Baum, 1901, p. 42) of knowing a greater amount than intended by almost looking at the foreheads of his family highlights the immersive qualities shown with AR—and although depicted negatively, the possibilities that will be discussed later show that super imposed information is one of the core principles that makes AR so unique. Despite this, Bob’s self-control needed to personal set boundaries in relation to technology, is one you can directly compare to our present societies overload of internet information. The prospect of making the accessibility to see information even easier than the little boxes we constantly carry with us now, does call into question one of the more controversial aspects of augmented reality.

![]() Despite Baum’s vision being

deeply dystopian, “The Character Marker” (Baum, 1901, p. 42) highlights two

factors in relation to AR. The first is that for many years that the idea

superimposing information onto the physical world, has been predicted and a

point to which technological development has been headed. Second, is the

underlying warning that this technology that wields much power must be used

with caution.

Despite Baum’s vision being

deeply dystopian, “The Character Marker” (Baum, 1901, p. 42) highlights two

factors in relation to AR. The first is that for many years that the idea

superimposing information onto the physical world, has been predicted and a

point to which technological development has been headed. Second, is the

underlying warning that this technology that wields much power must be used

with caution.

The next early anticipation of AR would be over 60 years later in a less fantastical manner, by American computer scientist, Ivan Edward Sutherland.

Universally known as the “father of computer graphics” (Hosch, no date)—credit to his innovative software ‘Sketchpad’, ancestor of graphical user interfaces (GUI)—Sutherland wrote a fundamental essay in 1965, "The Ultimate Display” (Sutherland, 1965). Within, he writes an extraordinary speculation of the trajectory of technology that is important in the development of the AR. This text opened up new perspectives on the capabilities of virtuality—suggestions that question and compete with the physical world. It is important to note that a ‘display’ in the sixties, does not necessarily coincide with the same interpretation today. What Sutherland refers to is a device capable of showing the output of a computer. He opens with:

“We live in a physical world whose properties we have come to know well through long familiarity. […] A display connected to a digital computer gives us the chance to gain familiarity with concepts not realizable in the physical world. It is a looking glass into a mathematical wonderland” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 508)

Analysing the text fifty years after being published, it is clear to see that the ‘wonderland’ Sutherland talks of, has materialised in the 21st Century. We have gained digital familiarity in terms of the internet, and prevalent use of mobile tech; He rightly so uses “we”, as a globally collective term, encompassing the entire human race in predicting its latest revolutionary advancement. As of 2019 it is estimated five billion of the world’s population own a mobile device (Silver, 2019). His incredible insight into the future is further supported by his prediction of the typewriter transforming into a laptop (“tomorrow’s computer user will interact with a computer through a typewriter” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 507)) and eye-tracking (“Machines to sense and interpret eye motion data can and will be built” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 508). Hence, it would be foolish to overlook Sutherland’s prognosis as an indicator to where Augmented Reality will expand. He concludes that:

“The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal. With appropriate programming such a display could literally be the Wonderland into which Alice walked.” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 508).

What Sutherland describes here seems to cross paths with the reality used in the Wachowski siblings directed film, The Matrix (1999). It could be argued that Augmented Reality used presently is the epoch to “The Ultimate Display” (Sutherland, 1965). Just as in the film—the machine would be an interactive neuro-simulation where the chair would not become real, but the sensation that would be felt sitting in it would. This quote also highlights how the computer scientist has prefigured the possibility of creating a constructed reality, whilst being conscious of the risks that are attached. Like Baum brings to light the moral dilemmas of the “Character Marker” in The Magic Key (Baum, 1901), the power of a tool that is spoken of in this essay could be likened that of a Divine creator. It is not surprising that following the chair, Sutherland continues with two disturbing examples of handcuffs and a bullet. Like the chair, the cuffs don’t become real but the sensation of being restricted is—the latter is harder to comprehend as it would call into question whether you would encounter death itself or experience the sensation (if so what would that be like?). It could be argued that as much as he wants to show the incredible possibilities that would be made available, the shocking nature of the examples could be an appeal to not childishly toy with technology such as this. If the software programming enabling a device such as “The Ultimate Display” (Sutherland,1965) was eventually as abundant as a mobile phone today, or the coding became open source, human nature would undoubtedly take its course, and be used immorally. Not only would this be an issue, but we would have to socially, politically, and environmentally adapt to a world were two indistinguishable realities (one of which was not real) were interchangeable. Sutherland offers a truly prodigious perspective on the fascinating pitfalls of the virtual realm.

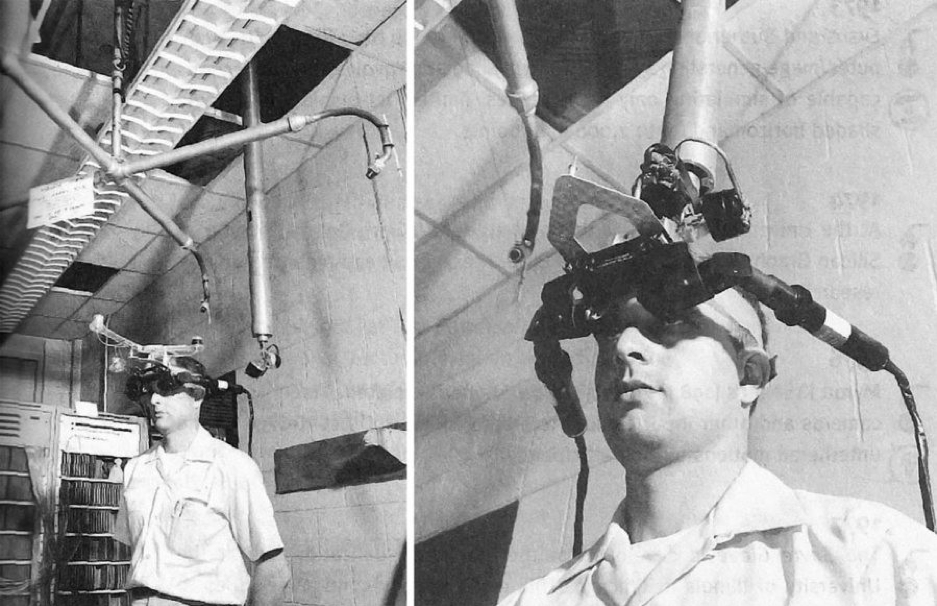

His next steps from this essay would also be a defining moment in the Augmented Reality timeline as he invents “The Sword of Damocles” (Sutherland, 1968)—the first head-mounted display (HMD) with see through optics. Built in his Harvard University Laboratory, the weight of the display meant that object had to be suspended from the ceiling—leading to the name referencing the ancient moral parable. The devices main components consisted of two protruding cathode ray tubes that had to be held by the user when worn. However, despite being confided to a limited “six feet in diameter and three feet high” (Sutherland, 1968) area, and the “mechanical head position sensor [being] rather heavy and uncomfortable to use” (Sutherland, 1968), the “relatively crude system” was successful in creating a “three-dimensional illusion [that] was real” (Sutherland, 1968). As he underlines in his report on the machine (A Head-mounted three-dimensional Display, Sutherland, 1968), “generating a perspective image of the three dimensional information is relatively easy” (Sutherland, 1968), yet computing the proportions in real time hindered development, especially regarding the hidden line problem (“The only existing real-time solution […] is a very expensive special-purpose computer at NASA Houston” (Sutherland, 1968)). Even with these mechanical issues that would only be improved with extensive processing improvements, fellow renowned American computer scientist and psychologist J. C. R. Licklider shared Sutherlands enthusiasm after testing The Sword of Damocles. He reflected:

“When I saw the demonstration, the hardware was not finished, and the situation was just an outline room with windows, a door, and a geo-metrical piece of statuary. Even at that, it was quite an adventure. Given situations defined by thousands of line segments, one could surely create some exciting experiences—and probably some very significant ones.” (Licklider, 1969, p. 618).

Indeed, Licklider was right in speculating the possibility of creating “some very significant” experiences (Licklider. J, 1969, p. 618) with AR, highlighting how we are headed to a technological immersive world. Throughout the seventies and eighties, computer engineers and graphic artists such as Myron Krueger, Dan Sandin and Scott Fisher, experimented with an array of concepts that mixed human interaction with computer-generated overlays. However, it was only during the mid eighties and nineties that advanced computing performance helped propel Augmented Reality into an independent field of study.

![]()

![]() In 1992, the birth of the

term Augmented Realty first appeared with Caudell and Mizell’s paper (Augmented

Reality: An Application of Heads-Up Display Technology to Manual Manufacturing

Processes, Caudell, Mizell, 1992) after creating a HMD system that assisted

workers in an airplane factory. From there a rapid increase in wearable

computing began to evolve, notably, from creators like Steve Mann at MIT Media

Lab (WearCam project, 1995), Reikimoto and Nagao (NaviCam, the first

tethered hand-held AR display, 1995).

In 1992, the birth of the

term Augmented Realty first appeared with Caudell and Mizell’s paper (Augmented

Reality: An Application of Heads-Up Display Technology to Manual Manufacturing

Processes, Caudell, Mizell, 1992) after creating a HMD system that assisted

workers in an airplane factory. From there a rapid increase in wearable

computing began to evolve, notably, from creators like Steve Mann at MIT Media

Lab (WearCam project, 1995), Reikimoto and Nagao (NaviCam, the first

tethered hand-held AR display, 1995).

As the displays utilised shrinking automation, condensing into devices that are more recognisable to the present day, it was a software platform at the turn of the century that allowed Augmented Realty to be more widely recognised—ARToolKit (1999). Released in 1999 by Hirokazu Kato and Mark Billinghurst, ARToolKit (1999) was the first open-source software platform that allowed users to produce their own AR creations. The programme “uses video tracking libraries [to] calculate the real camera position and orientation relative to physical markers” (Lamb, n.d.) in the form of black and white fiducials. Essentially these cards can be printed on any home computer which made the free software very appealing to the casual computer scientist. With the increased availability of webcams in conjunction with clever software design, ARToolKit was an instant success; even several years later in 2004 with 160,000 downloads in a year (Lamb, n.d.).

After 2000, the miniaturisation of technology allowed mobile computing to hardwire themselves into our standard of living; Evidence of this is seen by the dramatic increase in mobile phone ownership in the UK, from a mere 28% in 1999, to 76% in 2003 (O'Dea, 2019). With this shift augmented reality devices have also grown increasing powerful.

Famous example “Google Glass” released in 2013, failed incredibly despite its massive anticipation. This could be attributed to Google’s lack of foresight by clearly defining why glasses would advance the general public’s lifestyle (Yoon, 2018). In contrast to this, recent examples—especially in the entertainment/gaming industry—are proof that AR does have a position in the lives of many, combined with the incredible advances in computer-generated imagery. Start-up company Magic Leap has been seeing lots of interest, totalling a huge $2.6 billion (U.S. dollars) (Matney, 2019). However, with a steep starting price at $2,295 (U.S. dollars) it is unlikely to become an abundant house-hold gadget the near future. When compared other affordable emerging technology like smart devices, Google’s “Echo Dot” has a starting price of only £24.99. In spite of the enormous cost for one device, global AR (combined with VR) spending is forecast to be $18.8 billion (U.S. dollars) (International Data Corporation, 2019) in 2020, suggesting that AR amalgamation is imminent.

CHAPTER TWO—HISTORY OF ART AND TECHNOLOGY IN EXHIBITION SPACES

To anticipate the impact Augmented Reality will have in future exhibition spaces, analysing how institutions have previously presented and received art and technology work will provide a clearer standpoint. As well as this, it is also interesting to highlight the creative benefits in the collaboration of art and science.

In comparison to the complex digital landscape we see presently, Augmented Reality is one of the few technologies that still feels relatively fresh to the general public. Just as the examples that will be discussed sent shockwaves through the art world at the time, AR has the possibility to engage with audiences that echo similar reactions. Hence, for this chapter I have focused on two exhibitions that showcased pioneering artists, scientists, and machines who crossed the boundary of art and science.

The progress of art, science and technology merging was gradual and intermittent. Examples like Naum Gabo’s “Standing Wave” (1920), and Monoly-Nagy’s “Licht-Raum-modulator” (1930) during the 1920/30s used scientific apparatus as a new model to explore ideas of space and time; However, it was at the mid-point of the 20th century that more digital forms took hold. Though the fifties did not represent the fusion of these fields, these years were a catalyst for digital experimentation. As respected British art critic, writer and curator, Jasia Reichardt, put in her colloquium at National Academy of Sciences, “[…] it happened in the studios of individual artists, it happened in collaborative projects, and it gathered momentum in discussions about art and science.” (Reichardt, 2018). In this quote, Reichardt alludes a similar secluded trajectory to the beginnings of AR evolution; Started in the independent studios of a progressive few who were fascinated in the potential of machinery. In this talk she highlights three very different developments that “[…] laid down the foundations for [those] connections” (Reichardt, 2018); The beginnings of kinetic art (in Paris), the launch of the ‘Jikken Kobo’ (in Japan) (translated as “Experimental Workshop”), and creation of the Gaberbocchus Common Room (in London). Though dispersed throughout the globe, it is from these influences, specifically kinetic art, that I discovered one of the most influential exhibitions of the century; “Cybernetic Serendipity” (Sutherland, 1968).

Coordinated by previously mentioned, Jasia Reichardt, “Cybernetic Serendipity” was displayed to the public at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) from 2nd August, to the 20th October 1968. Its significance was grounded in being the first international exhibition devoted to the relationship between technology and creativity. The collection showcased a diverse array of work from human resembling robots and dancing machinery, to poems, paintings and films created by computers, demonstrating “some of the creative forms engendered by technology” (Reichardt, 1968, p. 5). The various range of outcomes attracted a broad audience to the ICA, “lur[ing] into Nash House people who never have dreamed of attending an ICA exhibition” (The Guardian, 1968, p. 390). This made press coverage on the whole very favourable. Indicative of many critics a review by the Evening Standard exclaimed: “Where in London could you take a hippy, a computer programmer, a ten-year-old schoolboy and guarantee that each would be perfectly happy for an hour without having to lift a finger to entertain them?” (Evening Standard, 1968, p. 390).

In light of the positive media, this enticed more visitors. By the end of the eleven weeks of exhibition, between forty thousand and sixty thousand visitors had passed through its doors—this had been the first time the ICA had the public lining up outside the gallery, making it one of their most successful projects.

![]() From

the 130 contributors, surprisingly (to someone of the 21st Century)

only a third of those involved were artists as personal computers were not

widely available during the sixties. Instead a majority were engineers,

mathematicians, architects and computer scientists. In addition to computers

being a rarity during this period, they were also lacking in user-friendly

systems so required much technical expertise. In some respects, this is one of

the core factors to why the exhibition was a success. Equipped with a breath of

programming knowledge and, their own set of digital painting tools, this form

of new media altered the shape of art. Void of preconception regarding their

occupation in relation to what ‘art’ is, engineers “who would never have put

pencil to paper, or brush to canvas” (Reichardt, 1968, p. 5) began creating the

most incredible images. This can be seen with, computer graphics pioneer Ken

Knowlton and, neuron researcher Leon Harmon’s “Gulls: studies in perception

II”.

From

the 130 contributors, surprisingly (to someone of the 21st Century)

only a third of those involved were artists as personal computers were not

widely available during the sixties. Instead a majority were engineers,

mathematicians, architects and computer scientists. In addition to computers

being a rarity during this period, they were also lacking in user-friendly

systems so required much technical expertise. In some respects, this is one of

the core factors to why the exhibition was a success. Equipped with a breath of

programming knowledge and, their own set of digital painting tools, this form

of new media altered the shape of art. Void of preconception regarding their

occupation in relation to what ‘art’ is, engineers “who would never have put

pencil to paper, or brush to canvas” (Reichardt, 1968, p. 5) began creating the

most incredible images. This can be seen with, computer graphics pioneer Ken

Knowlton and, neuron researcher Leon Harmon’s “Gulls: studies in perception

II”.

![]() These

smaller icons produced an image with fascinating multiple dimensions, and on

large scale (like that was presented in “Cybernetic Serendipity” which was

around 10ft long), could entice a viewer to examine each individual pattern.

These

smaller icons produced an image with fascinating multiple dimensions, and on

large scale (like that was presented in “Cybernetic Serendipity” which was

around 10ft long), could entice a viewer to examine each individual pattern.

With the background knowledge of the procedure, a superlative appreciation for the final artwork is gained. Though most of the ‘work’ is done by the computer the skill required to set up the computer programming is arguably an artform in itself. This notion is supported by fellow computer artist Frieder Nake, who states that the “art is done by the brain, not the hand. It liberates the artist from the limits of handicraft skills” (2010, p.56).

![]() “Cybernetic Serendipity” did not only create a

space where there was recognition for new media, but also made the experience

with computers enjoyable. Prior to the exhibition, there had been a period

where many felt “a desolation to be seen in art generally—that we haven’t the

faintest idea these days what art is for or about” (Shepard, 1968, p. 391).

There had also been an uncertainty around the conviction of new computer

technology as seen in a review—“Computers don’t bite, for it is a joyous

exhibition” (Daily Mirror, 1968, p. 391). People were fearful that technology

would “take over” (Stack,1968, p. 391), however by showing the artistic

possibilities made the seem less scary. As the ICA’s information officer said

at the time,

“Cybernetic Serendipity” did not only create a

space where there was recognition for new media, but also made the experience

with computers enjoyable. Prior to the exhibition, there had been a period

where many felt “a desolation to be seen in art generally—that we haven’t the

faintest idea these days what art is for or about” (Shepard, 1968, p. 391).

There had also been an uncertainty around the conviction of new computer

technology as seen in a review—“Computers don’t bite, for it is a joyous

exhibition” (Daily Mirror, 1968, p. 391). People were fearful that technology

would “take over” (Stack,1968, p. 391), however by showing the artistic

possibilities made the seem less scary. As the ICA’s information officer said

at the time,

“We want people to lose their fear of computers by playing with them and asking them simple questions […] In this show they will see these machines will only do what we want them too […] Happy accidents […] can happen between art and technology” (Stack, 1968, p. 391)

As many of the participants claimed not to be artists and there was no focus on achievement or technical accomplishment, the works had a vitality about them which made them fun to observe and interact with. As the Sunday Telegraph described, “Cybernetic Serendipity” is “…the most sophisticated amusement arcade you could hope to find around, an intellectual funfair without parallel.” (Shepard, 1968, p. 391).

This point is illustrated with one of the more famous works form the exhibition—“CYSP 1” (Shown in Figure 5 to the left of Gordon Pask’s “Colloquy of Mobiles”). Produced by Hungarian-born French artist, Nicholas Schoffer, “CYSP 1” (1956) was the first cybernetic sculpture ever made—its name combining two letters of the words ‘cybernetics’ and ‘spatio-dynamism’. Built in 1956, the project was inspired by the previously acknowledged kinetic art (not a movement but a name given to a group of several artists), and later that year it would perform with dancers (like in Figure 8.) at the ‘Avant-Guard’ festival in Marseille, in a ballet choreographed by Maurice Bejart. It consisted of flat strips and rods of polished steel that flapped like wings in response to sound movement, and coloured light in its vicinity. For example: As it was excited by blue light, silence or darkness, “CYSP 1” would move swiftly or change direction rapidly. However, in red light, bright light or being surrounded by noise, it would become calm. During the display, the unpredictable nature of the machine created a sensitivity that emulated organic life. This phenomenon only greatened our connection to computers and consequently to the art itself. Audiences began seeing them as equals as well as apparatus; highlighting how our culture was moving towards a more digital environment.

![]() The element

of fun that was weaved into “Cybernetic Serendipity”, helped inspire a post war

generation of artists into the field of computer arts; during a time of

positive political and social climatisation. Subsequently, this established a

groundwork for the decades of advances in digital image-making,

computer-generated-images (CGI) and eventually augmented reality artwork.

The element

of fun that was weaved into “Cybernetic Serendipity”, helped inspire a post war

generation of artists into the field of computer arts; during a time of

positive political and social climatisation. Subsequently, this established a

groundwork for the decades of advances in digital image-making,

computer-generated-images (CGI) and eventually augmented reality artwork.

The basis of the aforementioned influences during the fifties, had also birthed the unique association that created an exhibition performance predating “Cybernetic Serendipity”. The fascinating activities of the group “E.A.T.” (Experiments in Art and Technology) culminated between 13th – 23rd October 1966, during ‘9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering’. The non-profit organisation was formed on the basis of collaboration. As explained earlier, the complexity of programming in the sixties meant that if artists wanted to create an electronic piece, they would need the assistance of engineers. Billy Klüver, one of the founders of E.A.T. and an engineer from world-renowned Bell Telephone Laboratories (where Ken Knowlton also practiced), had seen a vision after working with artist Jean Tinguely. He “[…] realized that the engineers could help the artists […]; the engineers themselves could be the materials for the artists” (Klüver, 1995). In an interview from 1995 Klüver explains how

“The goal from the beginning was to provide new materials for artists in the form of technology. A shift happened because, from my own experience, I had worked in 1960 with Tinguely to do the machine that destroyed itself in the Garden of MoMA. At that time I employed—or coerced—a lot of my co-workers at Bell Labs to work on the project.” (Klüver, 1995).

Together with fellow Bells Labs peer Bob Rauschenberg, they invited a group of composers, dancers and theatre artists, as well as friends from the laboratory to begin meeting in early 1966. From the first meeting in Rauschenberg’s loft (Martin, 2013) artists began asking questions to what was physically and electronically possible from their ideas. Within the meeting, artists were assigned engineers, and eventually a theatre system was put in place that had ten performances; these would transform into “9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering” (E.A.T., 1966). Originally going to be located in Sweden’s capital, Stockholm, the performances were moved to New York in the 69th Regiment Armory. Within five days the collective of 10 artists and 30 engineers, turned the armoury into a theatre with bleachers, lights and speakers. Like “Cybernetic Serendipity” (1968), “9 Evenings” (1966) was also a success that collectively drew an estimated crowd of ten thousand.

One example that captures the immersive quality that could be possible with AR is Steve Paxton’s “Physical Things”. Coordinated with performance engineer Dick Wolff, “Physical Things”, was an architectural environment that occupied most of the Armory floor, and invited impromptu audience interaction. The polyethylene medium of which “Physical Things” was made consisted of long tunnels, several rooms, and a tower, held up with air generated by ten fans. Spectators could walk through the air supported structure and witness a multitude of auditory and visual events; from performers engaging in activities, slide projections and other vignettes (Morris, n.d.).

Best known for his work as a choreographer, Paxton used technology in this piece, as well as the relationship between dancer and non-dancer, to express experiences that involve the body and its intimate perception. Some areas along the route encapsulate the crowd in anatomical visions projected on the walls; pieces of moving flesh secluded by a black veil, a young woman engulfed in liquid crystals resembling blood circulation, and a set of twins observing passers-by. Whilst the tower is an altogether different environment that exposes the ears to a continuous hum.

Whist walking through participants are accompanied by a small radio receiver for picking up radio broadcasts—these are predominantly used at the end where a suspended net with wire loops transmit pre-recorded loops of sound including: a lecture on quitting smoking, animal noises, conversations, countdown for a space shuttle launch, gymnastic lessons and American commentators discussing the exceptional quality of Indian hockey players.

![]() As seen in a video taken by Barbro Lundestam documenting the piece, the

blank tunnels transport the audience into an obscure world where the myriad of

sounds bounce off the walls surrounding the viewer. As the tunnels change in

height and flow from the current of air, a sense of uncertainty anticipating

what lurks around the next corner, intensifies the sounds heard; distorting the

audiences’ perspective. Exhibitions, especially ones like Paxton has presented,

are a space in which allows people to escape the realm of the ‘real’ world. “Physical

things”’s multi-sensory experience, emphasises in particular how digital elements

in combination with physical objects, enhance viewer attachment to an artists

work.

As seen in a video taken by Barbro Lundestam documenting the piece, the

blank tunnels transport the audience into an obscure world where the myriad of

sounds bounce off the walls surrounding the viewer. As the tunnels change in

height and flow from the current of air, a sense of uncertainty anticipating

what lurks around the next corner, intensifies the sounds heard; distorting the

audiences’ perspective. Exhibitions, especially ones like Paxton has presented,

are a space in which allows people to escape the realm of the ‘real’ world. “Physical

things”’s multi-sensory experience, emphasises in particular how digital elements

in combination with physical objects, enhance viewer attachment to an artists

work.

CHAPTER THREE—THE RISE OF AUGMENTED REALITY AS AN ARTISTIC MEDIUM

As we’ve seen in chapters one and two, both augmented reality and the fusion of art and technology have developed along similar chronological timelines—both having their breakthrough eras throughout the sixties and have now matured into well distinguished fields. As they have integrated themselves into our culture, we now witness them too combining at the turn of the second decade, in the twenty-first century. With electronic equipment becoming increasingly affordable to the masses, a greater number of people have the ability to create digital artwork, and publish on—what Korean, American artist Nam June Paik calls—the “electronic superhighway” (Nam June Paik, 1995). Chapter three will therefore be an exploration into the rise of Augmented Reality art, using a couple of examples to demonstrate—Why is Augmented reality being used with art? How does the way we experience art through AR change our perception? In what ways are artists using this digital landscape to explore artistic possibilities? Will gallery spaces embrace this new approach to art?

The past two decades have seen an exponential growth in the advancement of technology. Ways of seeing and being are being subverted like humankind has never experienced before, as our minds and bodies become accustomed to a new digital reality. The “digital arena” (Blazwick, 2016, p. 20) has become so absorbed into our lives it’s impossible to think of how our world would function without it. This is only proven in a 2018 Global digital report from “We are Social” and “Hootsuite” that revealed, over four billion people around the world regularly use the internet. Furthermore, our relationship with computer screens lend us to spend on average three hours and fifteen minutes a day on our phones alone (Rescuetimeblog, 2019).

This sea of binary code in which we metaphorically swim, was eerily predicted and given an unofficial name in William Gibson’s fictitious 1984 novel “Neuromancer”—“cyberspace” (Gibson, 1984).

“Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators in every nation […] a graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind cluster and constellations of data […]” (Gibson, 1984, p. 20)

The essence of the term “cyberspace” (Gibson, 1984) fundamentally signifies homo sapiens natural yearning for connection through the lifeline of the digital universe. In a similar way, we can compare this to why ‘Art’ itself is so important. A quote, from previously mentioned kinetic artist, Jean Tinguely (Tinguely and Klüver worked on a kinetic sculpture that prompted Klüver to begin E.A.T.) explains how “Art is the distortion of an unendurable reality [...] Art is correction, modification of a situation; art is communication, connection [...] Art is social, self-sufficient, and total.” (Tinguely, 1960).

It is not surprising then that individuals are drawn to explore the “unthinkable complexity” (Gibson, 1984) through visual means, as well as using it as a tool itself. In a similar fashion to how the artists, composers and performers in E.A.T’s “9 Evenings”(1966) and the work displayed at “Cybernetic Serendipity” (1968) utilised technology to extend their range of expression, we are now seeing artists emulate this with augmented reality devices.

One creator that is an advocate for AR artwork is Nancy Baker Cahill. Based in Los Angeles, United States of America, Cahill captures the stories of individuals and utilises augmented technology publish publicly. “Interpreting the body as a site of struggle and resistance” (Cahill, 2018), Cahill’s most common medium, graphite pencils, are used to form other-worldly organic forms. Through working with the non-profit organisation of “Homeboy”, which redirects gang-involved and formally incarcerated youths, she found an immense value in working collaboratively. A touching project called “Bullet Blossoms” (2010), which involved “Homeboy” members creating collages, underlines the significance of gallery spaces available to all walks of life. During her Tedx Talk in 2018 she expressed how an “art gallery doesn’t have to be in a forbidding or exclusive venue. An art gallery doesn’t even need walls.” (Cahill, 2018). Her augmented reality work became a testament to this.

![]() Whilst struggling on “Surds”

(Cahill, 2016), inspired by Susan Brison’s book “Aftermath” (Brison,

2002), she had a breakthrough when a friend proposed working in virtual reality

(VR). After trialling mixed media, she discovered VR deconstructed the analogue

graphite drawings in a manner that was “rich with content and intention”

(Cahill, 2018). With the ability to move through the levitating digital

sculptures, the viewer was immersed in ways physical material is incapable. Not

only was drawing in three dimensions (using a VR headset) an “[…] almost

ecstatic experience […]” (Cahill, 2018), she found that the medium was so

powerful that many audiences recall “feeling [her work] in their bodies”

(Cahill, 2018). This new selection of work was to be named “Hollow Point”

(2018). After an exhibition, one woman took the headset off in tears and

another said, “I can’t tell if I’m in heaven or hell” (Cahill, 2018). In light

of this encounter, Cahill realised VR’s effectiveness in providing empathy,

however the headset still created an “exclusive” viewing.

Whilst struggling on “Surds”

(Cahill, 2016), inspired by Susan Brison’s book “Aftermath” (Brison,

2002), she had a breakthrough when a friend proposed working in virtual reality

(VR). After trialling mixed media, she discovered VR deconstructed the analogue

graphite drawings in a manner that was “rich with content and intention”

(Cahill, 2018). With the ability to move through the levitating digital

sculptures, the viewer was immersed in ways physical material is incapable. Not

only was drawing in three dimensions (using a VR headset) an “[…] almost

ecstatic experience […]” (Cahill, 2018), she found that the medium was so

powerful that many audiences recall “feeling [her work] in their bodies”

(Cahill, 2018). This new selection of work was to be named “Hollow Point”

(2018). After an exhibition, one woman took the headset off in tears and

another said, “I can’t tell if I’m in heaven or hell” (Cahill, 2018). In light

of this encounter, Cahill realised VR’s effectiveness in providing empathy,

however the headset still created an “exclusive” viewing.

By transforming the artwork into augmented reality through a free app, Cahill broadcasted them, allowing users to materialise her drawings in the ‘real world’ through their smartphones or tablet. Additionally, she released “Margin of Error” (2019). Emerging from the terrain like entities from parallel universes, both crystal-like sculptures are animated in such a way that embodies organic life—echoing “CSYP-1” from “Cybernetic Serendipity” (1966). Receiving a “mind-blowing” (Cahill, 2018) response, her work highlights the positive aspects AR has which can only evolve into greater accomplishments. This could be through augmented glasses as designer Geoffrey Lillemon suggests “[…] once real-time 3D mesh generation becomes more readily available, then we can wear […] ‘art goggles’ and be able to see a 3D version of our reality in real time. […] we can start thinking of filtered experiences” (Lillemon, 2013). The success of “Hollow Point” (Cahill, 2018) could be credited to having an equally stimulating experience viewed in VR, but with the convivence of mobile technology. It allows audiences to still feel connected to the real world and engage with people around them, whilst simultaneously viewing “concepts not realizable in the physical world” (Sutherland, 1968).

![]()

This works exceptionally well in a recently developed L.A. city-wide project that Cahill is advocating, “Battlegrounds” (2019), using GPS to ‘lock’ sculptures to historically significant locations. In collaboration with twenty-four local artists, “Battlegrounds” (2019) is an “[…] unapologetically political project, and does no environmental harm in a region of the country which is most vulnerable to climate change.” (4thwallapp, 2019) By fixing the artwork appropriately to the surroundings, blurring technology with existing architecture, artists have greater control over visual effect consumed—with the secondary benefit of not physically harming the location (although it could be argued that the electricity used in making and viewing the pieces could be just as environmental impactful).

The application of geographic site-specific augmented reality is also used in Freize Art Fairs, first augmented reality artwork by Korean artist, Koo Jeong A. Titled “Destiny” (2019), three sculptures can be found dispersed through the historic Regents park, London. Viewable through downloading the “Acute Art” app, the three ice blocks that hover above members of the public are as indistinguishable as physical sculptures; adding an entertaining and philosophical element in relation to the classical environment it is based. The material qualities added in the production allow for reflections taken from the camera, integrating it further into the space, allowing viewers to focus poetic nature of the piece, opposed to seeing it as solely a digital image. As Daniel Birnbaum, director at Acute Art, excitingly says “It looks just as realistic as the sculpture next to it. If you take a photo of it or you send it your friends, they will not be able to tell whether it is real or virtual […]” (Birnbaum, 2019).

The temporary exhibition held between the third to 6th of October 2019, is being represented again at Waddesdon Manor from 1st February 2020 demonstrating another positive attribute of augmented reality artwork—being able to reproduce art identically through taking the original file and publishing them anywhere through a computer.

An altogether different performance piece exhibition applied renowned “Magic Leap” software in Marina Abromovic’s “The Life” (2019). Held at the Serpentine Gallery, London, the Serbian artist, writer, and films maker, explores the relationship between performer and audience through a nineteen-minute production. Visitors are given spatial computing devices on arrival and witness the display from a five-metre roped circle in the centre. Despite Abromovic’s optimistic hopes, commenting “[…] this is the first time an artist has used this technology to create a performance […]”, a Guardian review deems it “[…] too slight to hold [the audiences] attention.” (Jones, 2019). In comparison to Cahill’s work, “The Life” (2019) consequently does not exert the same emotional influence, largely down to its absence of immersiveness. The five-metre space in-between does not lend itself to the benefits of using augmented reality in art, as seen in Magic Leaps other latest “Undersea” (2019) development; where spatial computing allows for underwater corals to be placed in the comfort of the user’s home. Thought it does well to comment on the artist’s long-standing fascination with the notion of material absence, Abromovic is aware that “this experiment is just the beginning [and hopes] that many other artists will follow [her] and continue to pioneer Mixed Reality as an art form” (Abromovic, 2019).

![]()

![]()

CONCLUSION

My personal aim of this dissertation was to expand my knowledge of augmented reality in relation to my extensive fascination with the future of art. Hence, this conclusion will be a summary of the discoveries I have made. The research for this thesis has diverted me to areas of augmented reality and the collaboration of art and technology, that I never anticipated when initially drafting my intention. Through investigating the complex history of both subjects, the plethora of examples prove our species natural drive to propel the digital creative capabilities of spatial technology, with astounding outcomes.

Chapter one outlines the birth of augmented reality, exploring the hopes and aspirations of an emerging technology. We see how science fiction in Baum’s novel “The Master Key” (1901) was the initiator that inspired generations to push a once thought impossible form of technology. Following this, perhaps one of the most fundamental scientists from this era who provides further insight is, Ivan Sutherland. His incredible work in conjunction with his habitual nature to expand the possibilities of the ‘display’, not merely shaped the luminescent screens we are encompassed by presently but established a voyage into the realm of mixed realities.

In a similar fashion, chapter two explores how art was influenced by the involvement of digital technology, principally in association with exhibitions. As seen through one of the most profound exhibitions of the twentieth century, “Cybernetic Serendipity” (1968) captivated the interest of almost anyone who walked through the ICA’s doors. Jasia Reichardt’s collection demonstrated to a post-war generation, the range of expression available to artists once they experimented through digital means. Between two once seemingly disconnected sectors, collaboration like in the case of Billy Klüver’s “9 Evenings” (1966), presented through digitised exhibition performances can elevate the feeling of immersion.

Chapter three delves into the contemporary uses of spatial technology in a wired culture. As a direct result of changing technological conditions, the ever-growing relevancy of the “digital arena” (Blazwick, 2016) in our lifestyles has led to devices becoming more accessible to artists. Additionally, through the emergence of spatial technology and pioneers of digital artwork, the rise of contemporary augmented reality art has allowed for previously unimaginable concepts to reshape our relationship with gallery spaces. Nancy Baker Cahill challenged traditional means of drawing by transforming them in VR. However, it was the transition into AR that ultimately connected her work to an audience in ways she had never previously visualised. Accompanied with new “Magic Leap” headsets, Marina Abromovic’s “The Life” (2019) is a fascinating example of what is anticipated as institutions like the Serpentine Gallery, embrace AR as an artistic tool. Nevertheless, Abromoic’s approach to mixed reality meant that she was unable to fully encompass the unique benefits of immersive mixed reality. In turn this factor was “The Life”’s (2019) downfall in the eyes of critics.

In the future, as shown by Magic Leap’s “Undersea” (2019) and Cahill’s “Battlegrounds” (Cahill, 2019) we are likely to see the exciting prospect of artists creating a new digital landscape, that can be witnessed within the walls of a gallery, or integrated within the exiting architecture of the physical world.

In my studio practice I have a genuine passion in excavating the history of subjects, and with the information, develop multifaceted outcomes by weaving elements of truth into them. As I plan to expand the breadth of mediums I use in my work to more digital influences, this thesis has broadened my expectations of what is truly possible. Through understanding the origins of augmented reality, I hope this will aid my own endeavours into the world of digital realities. Similarly, to Abromoic’s comment, I hope through my work “many other [peers] will follow [me] and continue to pioneer Mixed Reality as an art form” (Abromovic, 2019). Maybe someday we will eventually experience the wonderland Ivan Sutherland envisioned.

FIGURES:

No copyright intended.

Figure 1:

ORIGINAL DIAGRAM—P. Miligram and F. Kishino, (1994) Diagram of the "Mixed Reality" or "Reality-Virtuality" continuum. (Screen capture) Available at: http://etclab.mie.utoronto.ca/publication/1994/Milgram_Takemura_SPIE1994.pdf

Figure 2:

Cory. F. Y. (1901) The Character Marker (Illustration) Available at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/45347/45347-h/images/image26.jpg

Figure 3:

No Author (1968) The Sword of Damocles in use (Photograph) Available at: https://miro.medium.com/max/900/1*NtIkpTlzWLLBrVtmR9RsBQ.jpeg

Figure 4:

H. Kato and M. Billinghurst (1999) ARToolKit - Virtual Shared White Board (Photograph) Accessible at: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=803809

Figure 5:

No Author (1968) Gordon Pask, Colloquy of Mobiles, Installation view Cybernetic Serendipity (Scanned Photograph) p.199

Figure 6:

Knowlton . K. C. and Harmon .L. D. (1968) Gulls: studies in perception II (Scanned print) p.86

Figure 7:

Knowlton . K. C. and Harmon .L. D. (1968) Tone scale of symbols used in producing the "Telephone: Studies in perception I" (Scanned print) p.87

Figure 8:

Schoffer. N. (1965) "CYSP 1" with a dancer from French magazine 'TOUT SAVOIR' (Photograph) Available at: http://cyberneticzoo.com/cyberneticanimals/1956-cysp-1-nicolas-schoffer-hungarianfrench/

Figure 9:

Moore .P. (1966) Steve Paxton, Physical Things (Scanned photograph) New York City, US. p. 95 - Breitwieser. S and Museum der Moderne Salzburg Mönchsberg (2015) E.A.T. : Experiments in art and technology

Figure 10:

Cahill .N.B. (2017) Hollow Point 101 (VR still) Available at: https://nancybakercahill.com/artwork/vr-projects

Figure 11:

Wheeler. D. (2019) "Margin of Error" Augmented Reality drawing (AR still) alton Sea State Recreation Visitor Center Available at: https://nancybakercahill.com/artwork/vr-projects

Figure 12:

K. Jeong A (2019) Destiny viewed through Acute Art app (Photograph) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/sep/17/frieze-london-installs-first-augmented-reality-work-regents-park

Figure 13:

Richards. H. (2019) Marina Abramović: The Life (Installation View, 19 – 24 February 2019, Serpentine Galleries) (Photograph) Available at: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/exhibitions-events/marina-abramović-life

Figure 14:

Magic Leap (No date) Undersea (Photograph) Available at: https://uploadvr.com/siggraph-magic-leap-undersea/

︎︎︎

CONTENTS

1) Introduction

2) Chapter One—A brief history of augmented reality.

3) Chapter Two—History of Art and Technology in exhibition spaces.

4) Chapter Three—The Rise of Augmented Reality as an artistic medium.

5) Conclusion

INTRODUCTION

Augmented reality (AR); most commonly associated with the release of Nintendo's "Pokemon Go", rose the medium's relevance in the summer of 2016. With over a billion downloads as of February 2019, the game has one of the highest number of AR game users of all time. However, this emerging technology is more than just a gaming gimmick. In my practice of graphic design, I have witnessed increasing levels of this technology being used in company branding, such as the work being created at design studio Widen + Kennedy’s Department of New Realities. This has intrigued me to learn more about the origins of the field. In a world where screens are more abundant than ever before, the thought of digital information merging itself with the quotidian lifestyle does not seem an overly distant improbability. It’s contemporary application in art institutions is also fascinating, and leads me to wonder, as artists have become so familiar with digital technology, how will they use augmented reality as an expressionist tool?

Prior to exploring the implications of AR, it is essential to first outline the parameters of the technology and how it differs from other visual mechanics that we experience. Commonly misunderstood for its cousin, virtual reality (VR), both fall under the bracket of the “mixed reality continuum” (Miligram, Kishino, 1994, p. 83) coined by Milgram and Kishino as the “[…] merging of real and virtual worlds somewhere along the “virtuality continuum” which connects completely real environments to completely virtual ones.” (Miligram and Kishino, 1994, p.83). This idea is illustrated more clearly in Figure 1[Right] that shows how MR captures all possible combinations of real and virtual environments.

This blending of two worlds, the physical and the digital, and our relationship with it is what I find fascinating. By witnessing this composite view, an underlying level of uncertainty is felt trying to observe what is ‘real’ and what is not. The user becomes vulnerable to the boundless potential of the digital world, where depending on the ingenuity of an artist, it possible to observe literally anything.

If it is being used in a practical manner, for instance scrolling through your emails whilst commuting to work, this vulnerability is not so clear. However, through the medium of art, that specifically is created to provoke questions and tap into our emotional state, this vulnerability is a gateway that can lead to profound sensory experiences that we have never seen before.

With this small introduction to AR, the first chapter will investigate a brief overview, focusing on the genesis of the technology; Where did AR come from? What were the intentions of the pioneers? Following this, the second chapter will explore how art was influenced by the involvement of digital technology, in an act to understand if an emerging technology will be accepted by institutions. Finally, the third chapter will conclude with an investigation and analysis into contemporary uses of augmented art as a result of changing technological conditions.

CHAPTER ONE—A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUGMENTED REALITY

To comprehend how a technology will advance, it is crucial to understand where it has come from; the pioneers, first engaging with the concept, the boundaries in which it has overcome as well as the experimentalist ways it has been used. As well as this, it is imperative to examine the existing technologies surrounding the field. Hence, this chapter will be brief guide through the extensive history of Augmented Reality (AR) development, analysing significant seminal examples—focusing in particular on Ivan Sutherland’s work that catapulted the essence of AR into reality.

The concept surrounding AR could arguably surfaced over a century ago in Frank Baum’s 1901 illustrated novel “The Master Key: An Electrical Fairy Tale.” Though intended for children, Baum had foreseen the capabilities of electricity, and within the book had fabricated a number of electric inventions; one being a pair of glasses foreshadowing some characteristics we associate with AR. In the text, a boy named ‘Bob’ whose fascination with electricity summons a Demon that bestows him with nine of these electric creations. For the purpose of this essay “The Character Marker” (Baum, 1901, p. 42) is of most use.

“It consists of this pair of spectacles. While you wear them every one you meet will be marked upon the forehead with a letter indicating his or her character. The good will bear the letter 'G,' the evil the letter 'E.' […] Thus you may determine by a single look the true natures of all those you encounter."” (Baum, 1901, p. 42)

Though the “natural forces” that the spectacles are measuring are very likely not to be proven by science, the importance of this example is the instigation of AR. This is the first time in written literature that the concept of projecting graphic information onto a viewer’s perspective has been seen. An interesting point to study in this case is the protagonist’s use and vigilance of the device. In the chapter following being given the spectacles ‘Bob’ deliberates trialling them on his family. However, “[…] a sudden fear took possession of him that he might regret the act forever afterward.” (Baum, 1901, p. 42). In this example, Bob’s “fear” (Baum, 1901, p. 42) of knowing a greater amount than intended by almost looking at the foreheads of his family highlights the immersive qualities shown with AR—and although depicted negatively, the possibilities that will be discussed later show that super imposed information is one of the core principles that makes AR so unique. Despite this, Bob’s self-control needed to personal set boundaries in relation to technology, is one you can directly compare to our present societies overload of internet information. The prospect of making the accessibility to see information even easier than the little boxes we constantly carry with us now, does call into question one of the more controversial aspects of augmented reality.

The next early anticipation of AR would be over 60 years later in a less fantastical manner, by American computer scientist, Ivan Edward Sutherland.

Universally known as the “father of computer graphics” (Hosch, no date)—credit to his innovative software ‘Sketchpad’, ancestor of graphical user interfaces (GUI)—Sutherland wrote a fundamental essay in 1965, "The Ultimate Display” (Sutherland, 1965). Within, he writes an extraordinary speculation of the trajectory of technology that is important in the development of the AR. This text opened up new perspectives on the capabilities of virtuality—suggestions that question and compete with the physical world. It is important to note that a ‘display’ in the sixties, does not necessarily coincide with the same interpretation today. What Sutherland refers to is a device capable of showing the output of a computer. He opens with:

“We live in a physical world whose properties we have come to know well through long familiarity. […] A display connected to a digital computer gives us the chance to gain familiarity with concepts not realizable in the physical world. It is a looking glass into a mathematical wonderland” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 508)

Analysing the text fifty years after being published, it is clear to see that the ‘wonderland’ Sutherland talks of, has materialised in the 21st Century. We have gained digital familiarity in terms of the internet, and prevalent use of mobile tech; He rightly so uses “we”, as a globally collective term, encompassing the entire human race in predicting its latest revolutionary advancement. As of 2019 it is estimated five billion of the world’s population own a mobile device (Silver, 2019). His incredible insight into the future is further supported by his prediction of the typewriter transforming into a laptop (“tomorrow’s computer user will interact with a computer through a typewriter” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 507)) and eye-tracking (“Machines to sense and interpret eye motion data can and will be built” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 508). Hence, it would be foolish to overlook Sutherland’s prognosis as an indicator to where Augmented Reality will expand. He concludes that:

“The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal. With appropriate programming such a display could literally be the Wonderland into which Alice walked.” (Sutherland, 1965, p. 508).

What Sutherland describes here seems to cross paths with the reality used in the Wachowski siblings directed film, The Matrix (1999). It could be argued that Augmented Reality used presently is the epoch to “The Ultimate Display” (Sutherland, 1965). Just as in the film—the machine would be an interactive neuro-simulation where the chair would not become real, but the sensation that would be felt sitting in it would. This quote also highlights how the computer scientist has prefigured the possibility of creating a constructed reality, whilst being conscious of the risks that are attached. Like Baum brings to light the moral dilemmas of the “Character Marker” in The Magic Key (Baum, 1901), the power of a tool that is spoken of in this essay could be likened that of a Divine creator. It is not surprising that following the chair, Sutherland continues with two disturbing examples of handcuffs and a bullet. Like the chair, the cuffs don’t become real but the sensation of being restricted is—the latter is harder to comprehend as it would call into question whether you would encounter death itself or experience the sensation (if so what would that be like?). It could be argued that as much as he wants to show the incredible possibilities that would be made available, the shocking nature of the examples could be an appeal to not childishly toy with technology such as this. If the software programming enabling a device such as “The Ultimate Display” (Sutherland,1965) was eventually as abundant as a mobile phone today, or the coding became open source, human nature would undoubtedly take its course, and be used immorally. Not only would this be an issue, but we would have to socially, politically, and environmentally adapt to a world were two indistinguishable realities (one of which was not real) were interchangeable. Sutherland offers a truly prodigious perspective on the fascinating pitfalls of the virtual realm.

His next steps from this essay would also be a defining moment in the Augmented Reality timeline as he invents “The Sword of Damocles” (Sutherland, 1968)—the first head-mounted display (HMD) with see through optics. Built in his Harvard University Laboratory, the weight of the display meant that object had to be suspended from the ceiling—leading to the name referencing the ancient moral parable. The devices main components consisted of two protruding cathode ray tubes that had to be held by the user when worn. However, despite being confided to a limited “six feet in diameter and three feet high” (Sutherland, 1968) area, and the “mechanical head position sensor [being] rather heavy and uncomfortable to use” (Sutherland, 1968), the “relatively crude system” was successful in creating a “three-dimensional illusion [that] was real” (Sutherland, 1968). As he underlines in his report on the machine (A Head-mounted three-dimensional Display, Sutherland, 1968), “generating a perspective image of the three dimensional information is relatively easy” (Sutherland, 1968), yet computing the proportions in real time hindered development, especially regarding the hidden line problem (“The only existing real-time solution […] is a very expensive special-purpose computer at NASA Houston” (Sutherland, 1968)). Even with these mechanical issues that would only be improved with extensive processing improvements, fellow renowned American computer scientist and psychologist J. C. R. Licklider shared Sutherlands enthusiasm after testing The Sword of Damocles. He reflected:

“When I saw the demonstration, the hardware was not finished, and the situation was just an outline room with windows, a door, and a geo-metrical piece of statuary. Even at that, it was quite an adventure. Given situations defined by thousands of line segments, one could surely create some exciting experiences—and probably some very significant ones.” (Licklider, 1969, p. 618).

Indeed, Licklider was right in speculating the possibility of creating “some very significant” experiences (Licklider. J, 1969, p. 618) with AR, highlighting how we are headed to a technological immersive world. Throughout the seventies and eighties, computer engineers and graphic artists such as Myron Krueger, Dan Sandin and Scott Fisher, experimented with an array of concepts that mixed human interaction with computer-generated overlays. However, it was only during the mid eighties and nineties that advanced computing performance helped propel Augmented Reality into an independent field of study.

As the displays utilised shrinking automation, condensing into devices that are more recognisable to the present day, it was a software platform at the turn of the century that allowed Augmented Realty to be more widely recognised—ARToolKit (1999). Released in 1999 by Hirokazu Kato and Mark Billinghurst, ARToolKit (1999) was the first open-source software platform that allowed users to produce their own AR creations. The programme “uses video tracking libraries [to] calculate the real camera position and orientation relative to physical markers” (Lamb, n.d.) in the form of black and white fiducials. Essentially these cards can be printed on any home computer which made the free software very appealing to the casual computer scientist. With the increased availability of webcams in conjunction with clever software design, ARToolKit was an instant success; even several years later in 2004 with 160,000 downloads in a year (Lamb, n.d.).

After 2000, the miniaturisation of technology allowed mobile computing to hardwire themselves into our standard of living; Evidence of this is seen by the dramatic increase in mobile phone ownership in the UK, from a mere 28% in 1999, to 76% in 2003 (O'Dea, 2019). With this shift augmented reality devices have also grown increasing powerful.

Famous example “Google Glass” released in 2013, failed incredibly despite its massive anticipation. This could be attributed to Google’s lack of foresight by clearly defining why glasses would advance the general public’s lifestyle (Yoon, 2018). In contrast to this, recent examples—especially in the entertainment/gaming industry—are proof that AR does have a position in the lives of many, combined with the incredible advances in computer-generated imagery. Start-up company Magic Leap has been seeing lots of interest, totalling a huge $2.6 billion (U.S. dollars) (Matney, 2019). However, with a steep starting price at $2,295 (U.S. dollars) it is unlikely to become an abundant house-hold gadget the near future. When compared other affordable emerging technology like smart devices, Google’s “Echo Dot” has a starting price of only £24.99. In spite of the enormous cost for one device, global AR (combined with VR) spending is forecast to be $18.8 billion (U.S. dollars) (International Data Corporation, 2019) in 2020, suggesting that AR amalgamation is imminent.

CHAPTER TWO—HISTORY OF ART AND TECHNOLOGY IN EXHIBITION SPACES

To anticipate the impact Augmented Reality will have in future exhibition spaces, analysing how institutions have previously presented and received art and technology work will provide a clearer standpoint. As well as this, it is also interesting to highlight the creative benefits in the collaboration of art and science.

In comparison to the complex digital landscape we see presently, Augmented Reality is one of the few technologies that still feels relatively fresh to the general public. Just as the examples that will be discussed sent shockwaves through the art world at the time, AR has the possibility to engage with audiences that echo similar reactions. Hence, for this chapter I have focused on two exhibitions that showcased pioneering artists, scientists, and machines who crossed the boundary of art and science.

The progress of art, science and technology merging was gradual and intermittent. Examples like Naum Gabo’s “Standing Wave” (1920), and Monoly-Nagy’s “Licht-Raum-modulator” (1930) during the 1920/30s used scientific apparatus as a new model to explore ideas of space and time; However, it was at the mid-point of the 20th century that more digital forms took hold. Though the fifties did not represent the fusion of these fields, these years were a catalyst for digital experimentation. As respected British art critic, writer and curator, Jasia Reichardt, put in her colloquium at National Academy of Sciences, “[…] it happened in the studios of individual artists, it happened in collaborative projects, and it gathered momentum in discussions about art and science.” (Reichardt, 2018). In this quote, Reichardt alludes a similar secluded trajectory to the beginnings of AR evolution; Started in the independent studios of a progressive few who were fascinated in the potential of machinery. In this talk she highlights three very different developments that “[…] laid down the foundations for [those] connections” (Reichardt, 2018); The beginnings of kinetic art (in Paris), the launch of the ‘Jikken Kobo’ (in Japan) (translated as “Experimental Workshop”), and creation of the Gaberbocchus Common Room (in London). Though dispersed throughout the globe, it is from these influences, specifically kinetic art, that I discovered one of the most influential exhibitions of the century; “Cybernetic Serendipity” (Sutherland, 1968).

Coordinated by previously mentioned, Jasia Reichardt, “Cybernetic Serendipity” was displayed to the public at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) from 2nd August, to the 20th October 1968. Its significance was grounded in being the first international exhibition devoted to the relationship between technology and creativity. The collection showcased a diverse array of work from human resembling robots and dancing machinery, to poems, paintings and films created by computers, demonstrating “some of the creative forms engendered by technology” (Reichardt, 1968, p. 5). The various range of outcomes attracted a broad audience to the ICA, “lur[ing] into Nash House people who never have dreamed of attending an ICA exhibition” (The Guardian, 1968, p. 390). This made press coverage on the whole very favourable. Indicative of many critics a review by the Evening Standard exclaimed: “Where in London could you take a hippy, a computer programmer, a ten-year-old schoolboy and guarantee that each would be perfectly happy for an hour without having to lift a finger to entertain them?” (Evening Standard, 1968, p. 390).

In light of the positive media, this enticed more visitors. By the end of the eleven weeks of exhibition, between forty thousand and sixty thousand visitors had passed through its doors—this had been the first time the ICA had the public lining up outside the gallery, making it one of their most successful projects.

With the background knowledge of the procedure, a superlative appreciation for the final artwork is gained. Though most of the ‘work’ is done by the computer the skill required to set up the computer programming is arguably an artform in itself. This notion is supported by fellow computer artist Frieder Nake, who states that the “art is done by the brain, not the hand. It liberates the artist from the limits of handicraft skills” (2010, p.56).

“We want people to lose their fear of computers by playing with them and asking them simple questions […] In this show they will see these machines will only do what we want them too […] Happy accidents […] can happen between art and technology” (Stack, 1968, p. 391)

As many of the participants claimed not to be artists and there was no focus on achievement or technical accomplishment, the works had a vitality about them which made them fun to observe and interact with. As the Sunday Telegraph described, “Cybernetic Serendipity” is “…the most sophisticated amusement arcade you could hope to find around, an intellectual funfair without parallel.” (Shepard, 1968, p. 391).

This point is illustrated with one of the more famous works form the exhibition—“CYSP 1” (Shown in Figure 5 to the left of Gordon Pask’s “Colloquy of Mobiles”). Produced by Hungarian-born French artist, Nicholas Schoffer, “CYSP 1” (1956) was the first cybernetic sculpture ever made—its name combining two letters of the words ‘cybernetics’ and ‘spatio-dynamism’. Built in 1956, the project was inspired by the previously acknowledged kinetic art (not a movement but a name given to a group of several artists), and later that year it would perform with dancers (like in Figure 8.) at the ‘Avant-Guard’ festival in Marseille, in a ballet choreographed by Maurice Bejart. It consisted of flat strips and rods of polished steel that flapped like wings in response to sound movement, and coloured light in its vicinity. For example: As it was excited by blue light, silence or darkness, “CYSP 1” would move swiftly or change direction rapidly. However, in red light, bright light or being surrounded by noise, it would become calm. During the display, the unpredictable nature of the machine created a sensitivity that emulated organic life. This phenomenon only greatened our connection to computers and consequently to the art itself. Audiences began seeing them as equals as well as apparatus; highlighting how our culture was moving towards a more digital environment.

The basis of the aforementioned influences during the fifties, had also birthed the unique association that created an exhibition performance predating “Cybernetic Serendipity”. The fascinating activities of the group “E.A.T.” (Experiments in Art and Technology) culminated between 13th – 23rd October 1966, during ‘9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering’. The non-profit organisation was formed on the basis of collaboration. As explained earlier, the complexity of programming in the sixties meant that if artists wanted to create an electronic piece, they would need the assistance of engineers. Billy Klüver, one of the founders of E.A.T. and an engineer from world-renowned Bell Telephone Laboratories (where Ken Knowlton also practiced), had seen a vision after working with artist Jean Tinguely. He “[…] realized that the engineers could help the artists […]; the engineers themselves could be the materials for the artists” (Klüver, 1995). In an interview from 1995 Klüver explains how

“The goal from the beginning was to provide new materials for artists in the form of technology. A shift happened because, from my own experience, I had worked in 1960 with Tinguely to do the machine that destroyed itself in the Garden of MoMA. At that time I employed—or coerced—a lot of my co-workers at Bell Labs to work on the project.” (Klüver, 1995).